By Stephen Carter

“What would a good Mormon video game play like?” It’s a question that has doubtless crossed the mind of many a Mormon gamer as he fires missiles at a giant mutant brain, or slices her way through a horde of zombies, or fattens up a princess.

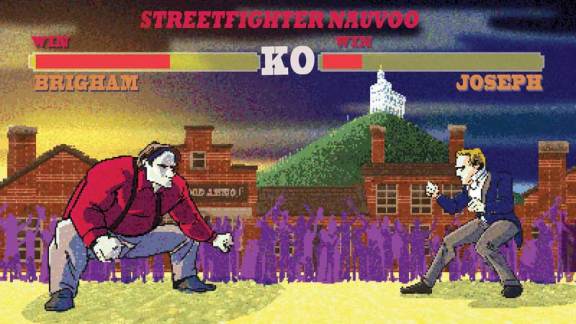

The first game ideas that come to mind might be something like Street Fighter Nauvoo, where characters from early Mormon history do battle for supremacy. Of course, being a Mormon video game, it would have to teach something, so we’d give each character special fighting moves that would sneak a few facts into the player’s brain. Joseph Smith could have a back-breaking stick-pull move; Brigham Young could mash his opponents with a covered wagon, and Eliza Snow could call on the help of a few heroic couplets.

Or maybe we could develop a game called Brigham Kong, where a pixelly pioneer guy climbs up logs and jumps over barrels to rescue his wife from Brigham’s harem.

The possibilities are endless—but also, admittedly, not all that Mormon. We may be using Mormon characters and borrowing from stereotypes, but when looking for a good Mormon video game, shouldn’t we be hoping for something a little deeper; something with more substance; something that could possibly tap the core of Mormon experience, theology, and worldview?

A similar question is contemplated at length in a book edited by Craig Detweiler, Halos and Avatars: Playing Video Games with God (Westminster John Knox Press). But in this case, the question is: What makes a game Christian?

In her chapter, Rachel Wagner provides a quick tour of video games that feature biblical themes or characters: games like Bible Fight where you can break face with Jesus, Moses, Eve, Satan, and even Mary. The fig leaf-clad Eve can use her serpent attack or call Adam in to kick some trash for her, though Noah’s ability to call in a wild animal stampede is more impressive. Or a player can use Mary’s heavenly teleportation ability to get her out of the tight spots her flying feet can’t. Moses can rain frogs on an opponent or hurl a couple of hefty commandments. Or if you want to let your fists fly outside the Judeo-Christian tradition, you can play Faith Fighter and rumble as Mohammed (with or without a face), Buddha, Budai, or Ganesha.

These games, of course, were mainly developed for laughs, and so I suppose we shouldn’t expect much depth from them. But as I found out, even when dealing with Christian development companies, it is still almost impossible to find a game that uses biblical characters, stories, and themes as anything more than pawns in the service of a trivial scenario.

For example, the Wisdom Tree company has been making Bible-based video games for more than 20 years. One of their most popular titles is Bible Adventure—three games stuffed into one NES-compatible cartridge. In the first game, “Noah’s Ark,” the player controls Noah as he picks up animals and carries them overhead to the ark. In “Baby Moses,” you play Moses’s mother as she tries to carry her diaper-clad infant (over her head) past enemies—many of whom, if they get their hands on the baby, will throw him in the water. And don’t miss out on Noah’s Ark 3-D, a first-person shooter (or, rather, slingshotter) where the goal is to shoot tranquilizers at an onslaught of homicidal goats before they batter Noah to a pulp. Please also give Jesus in Space a try; currently on sale for only $22.95!

These are the faithful games. The ones from people who purportedly take their religion seriously.

The Christian video game that got the most attention in Halos and Avatars was the Left Behind series, based on the popular religious apocalypse books by Tim LaHaye and Jerry Jenkins. The game takes place in ruined city streets where neutral characters wander among evil soldiers, military vehicles, and rumbling tanks. The player’s job is to convert as many neutral people as possible to God’s side and then mount an attack on evil forces.

How do you go about converting a neutral character to the Lord’s side? Well, first you build a relationship of trust, and then . . . just kidding. If your spirit meter is high enough, all you have to do is click on the desired characters and, in a shower of light, they’re born again and equipped to kick some Satanic tushie! And how do you fill your spirit meter high enough to perform such a miracle? Click on it with your mouse. Lots. If you happen to shoot an innocent bystander—or worse, stand near a rock concert—your spirit meter will plunge. But it’s nothing a few dozen repentant clicks can’t fix. The world of Left Behind, though dangerous, is a predictable and controllable world where all one has to do to succeed is follow the rules.

So what about Mormon video games? How do they stack up against mainstream Christian games?

My Google search revealed exactly two Mormon video games. The first, Outpost Zarahemla, is a goofy, space-based SimCity-type game. You play a humanoid missionary who is under the command of a fish-headed senior companion. He puts you in charge of a space station where your job is to keep the drivers of incoming spaceships happy by building power sources, lemonade stands, and rec centers that provide “good clean fun.” Oh, and you have to earn money. In fact, profit is so important that you can’t complete a level until you’ve earned a specified sum.

As the game continues, you are required to build family history centers (where some visitors learn that an ancestor was a fish), and other vaguely Mormon structures.

Some spaceships that come in are marked by an exclamation point. If you click them, they will ask you a churchy question such as “Are Mormons Christian?” (Answer: Yes); “How many books of Alma are there in the Book of Mormon? (Answer: One); and “What is a deacon’s duty?” (Answer: To help the bishop). Considering the game was released in 2004, it’s not too bad, and it has some humorous moments. But its religious elements are only tacked on—unless the core of Mormonism is making a profit.

The second game I found is called Brother Nephi’s Ultra-funtastic Point-and-click Adventure. It has been released in two parts thus far: the first getting Nephi into Jerusalem to acquire the plates of brass, and the second helping him find and kill Laban. A King’s Quest-style game, the player walks Nephi through various environments to locate and combine items that will help him complete his mission. For example, giving a cat to the camel causes the camel to run into a cafe and expose an illegal animal smuggler, thus allowing you to go up on a balcony to grab a blanket that helps you cross a mud barrier on the way to Laban’s house. But you have to get the poem first.

Umm, yeah. The causal chain doesn’t make a lot of sense there, but it does in the game . . . kind of. But that’s part of the game’s charm: its dry, free-associative sense of humor.

However, the game suddenly grows very strange when Nephi finds Laban. Until now, the tone of the game has been breezy and witty (though the amateurish voice acting destroys the ethos of the script). But suddenly, angelic music swells, and, as Nephi is bathed in an ethereal light, a deep, God-like voice quotes scripture about how one person may perish if it will save the souls of many.

Then the mood alters drastically again as the player is launched into a mini-game where Nephi is standing, sword drawn, over Laban’s body. The object is to land a swiftly moving line inside a small demarcated area—and it’s not easy. Each time you miss, Nephi’s sword comes down and eyeballs, fingers, and other body parts fly up. It’s funny. Really. But as I giggled and hacked, I was almost afraid I was going to be struck by lightning. The mini-game bumped me up against a question I had never thought about before: what are the tensions that make integrating video games and scripture so difficult?

In her Halos and Avatars chapter, “The Play is the Thing: Interactivity from Bible Fight to the Passions of Christ,” Rachel Wagner probes the same question, pointing out that though the story of Jesus Christ has been told in many a film, it has remained all but untouched in video games. She cites a few games where one can play characters who interact in peripheral ways with the Passion but none that actually give the player significant interactivity with the event itself.

She argues that, in contrast to film, where the narrative is laid out and permanent, video games liquefy the stories they touch because a player, not a writer or director, is in charge of the protagonist’s movements. Making the Passion the subject of a video game would throw the event and its interpretation into question. If the player isn’t skilled enough, Jesus might fail and the redemption of the world might not come to pass. Such a possibility strikes at Christianity’s foundations. And when you jiggle the pillars of people’s worldview, they tend to freak out.

Likely I was feeling something similar while I helped hack Laban’s head off: I was messing with a core story. Being one of the founders of Mormonism’s first satire magazine, The Sugar Beet, I’m not squeamish about tipping a sacred cow or two. But the murder of Laban is one of those stories that bears the markings of archetype.

Archetypes are stories that get told again and again because they have deep roots in essential aspects of human experience. The roots are so deep that even when thousands of years’ worth of people and institutions try to interpret the stories to favor their particular worldview, the stories still manage to retain their ability to lead thoughtful listeners into mystery.

Abraham’s attempted sacrifice of Isaac is one such story. Søren Kierkegaard, a Danish Christian philosopher, wrote an entire book, Fear and Trembling, exploring the mystery Abraham’s narrative points us toward: what is the nature of faith?

As Kierkegaard points out, if one of us found out that a man was taking his son to a mountain in order to sacrifice him, wouldn’t we try to stop him? Indeed, wouldn’t we have tried to stop Abraham? And what about Nephi? If Jerusalem’s finest had caught him chopping Laban’s head off, wouldn’t they have been justified in carting Nephi off to jail? If we had been nearby, wouldn’t we have tried to stop Nephi from committing his act? Taking a life is irrevocable no matter how good the intentions.

Kierkegaard’s explanation of Abraham’s story is that it is a metaphor for the radical subjectivity of faith, for the absolute exclusivity of one’s relationship with the divine. In other words, no one can in any way be a part of or understand your relationship with the divine; the relationship is exclusively between you and God. No outside observer can judge it. The story presents such a repulsive scenario to point to the impossibility of understanding Abraham’s relationship with the divine. The only way you could hope to understand another person’s faith is to live his or her life.

Nephi’s motivations for killing are a little more understandable than Abraham’s. After all, Laban had threatened the lives of Nephi and his brothers, Laban had also stolen their wealth, and Nephi believed that the plates of brass were essential to the success of his family’s divinely mandated journey. But this setup puts a new twist on the Abraham story. Abraham’s act seems next to insane and is rife with personal sacrifice, but Nephi’s act deprives him of no one he loves, gets an enemy out of his way, and secures him access to the plates of brass. He has everything to gain and nothing to lose by killing Laban. It seems unlikely that such a convenient and lucrative murder could be divinely mandated, especially since—unlike in Abraham’s story—Nephi actually does end a human life.

I can’t recall having ever been in a Sunday School class where someone questioned Nephi’s decision. The popular vote seems to be that Nephi did the right thing—the voters happily embracing the idea that God and Nephi were utilitarians (considering the life of one man to be of less moral weight than the religious cohesion of Lehi’s descendants, and therefore expendable). But archetypal stories are structured to ignite exploration, not instill certitude. Nephi’s story is meant to fracture our worldview, not stabilize it.

Which brings me back to my original question: what element could imbue a game with a resonantly Mormon core? It would be our unique archetypal stories, presented in such a way that the player would have to grapple with the tensions that make the stories powerful.

But how might such a game unfold? Mark Hayse presents an interesting template in his Halos and Avatars chapter “Ultima IV: Simulating the Religious Quest.”

At the beginning of this fantasy role-playing game released in 1985, the player is presented with a series of ethical dilemmas; for example: “Thou art sworn to uphold a Lord who participates in the forbidden torture of prisoners. Each night their cries of pain reach thee. Dost thou, A) show Compassion by reporting the deeds, or B) Honor thy oath and ignore the deeds?” Notice how the choices pit two virtues against each other? There doesn’t seem to be a correct answer—only a revealing one. The answers the player provides shape the character he or she will play. In a way, the character is an embodiment of the player’s worldview.

The player wanders through Brittania, encountering other characters—friendly and otherwise—monsters, animals, and difficult situations. The goal is to perfect the character in each of the eight virtues, but no guidance is offered. As players interact with the game, their decisions affect their character’s virtues. In all cases, players have to sacrifice one thing to gain another. If they flee from an unwinnable battle, they lose valor points, but they also live. If they cheat the herbs woman so that they can have enough money to buy an essential item, they gain the item, but lose honesty points.

But here’s the twist. The game never shows players how many points they have in each virtue, or the consequences their actions have on their virtues. As Hayse writes: “Gradually, players come to realize that the quest for virtue demands ongoing ethical self-assessment. Every interaction with the subjects and objects of Britannia requires critical reflection.” Some of the questions the player is forced to contemplate include: “What is the right thing to do when I am attacked by others? . . . If I find something of value on my journey, under what conditions may I claim it as my own? . . . When asked to share financial or physical resources with others, how much should I share? . . . Are there certain tools that I should not employ in the service of virtue? Or does the virtue sanctify every tool in order that the end justifies the means?” Now there’s a question for Nephi!

A careful study of scripture and Church history reveals the fact that our world and its inhabitants are complex and ever-changing. It might be comforting to think that one need only “choose the right” in order to increase one’s spiritual stature and avoid the evils of the world, but it’s a false comfort. Zion’s Camp was a grab-bag of death, failure, and miracles. Many of Alma and Amulek’s converts were burned to death by their own neighbors. Ammon’s converts had even less luck, being constantly dogged by murderous armies. Sure, we can offer mollifying explanations for these difficult situations, but they serve only to neuter the exploratory potential these stories offer.

The Book of Mormon seems very clear in its conviction that good intentions don’t always produce good results. What if we built a game around that idea? Could we make Alma into a video game character, eject him from King Noah’s palace and watch as the player attempts to bring people together around a common, but revolutionary, faith? How would he spread his gospel? What parts of the gospel would he emphasize? How would the people react to those particular principles? Whom would Alma trust with power in his fledgling church? How would he deal with the attacks of King Noah’s army? What decisions would he make in order to keep his people alive in the wilderness? How would he secretly boost his people’s morale while they are enslaved by the Lamanites? What sacrifices will he need to make to achieve his goals? How will the consequences of his decisions affect him and the people who follow him?

At first, it might seem that developing such a game would be prohibitively expensive, especially for such a small audience. But making a game as an app or as a Flash game to be distributed on the internet can be relatively inexpensive. The graphics don’t have to be the greatest, as Ultima IV proves, and neither does the music. What really matters is how skillfully room is made for value-laden, consequence-ridden choices, where something like a virtual soul can be forged.

Video games could prove themselves to be a great medium in which to create a post-modern midrash, where we could not only re-envision our stories, but relive them; drawing out the archetypal power many of them possess, making them more personally relevant.

Besides, think of how the seminary program would boom if the kids knew that they were required to play awesome video games for half an hour a day.